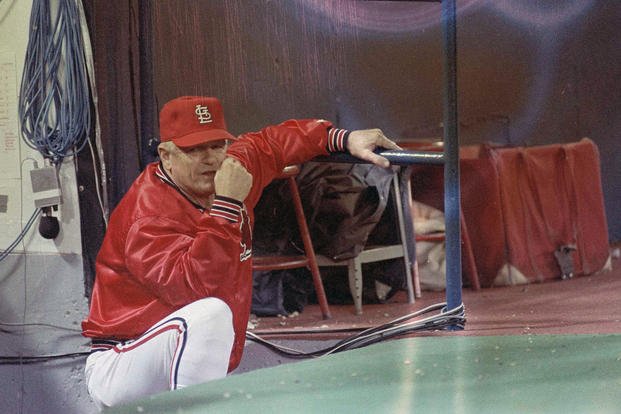

With a flattop haircut, pointed opinions and a Midwestern sensibility, Whitey Herzog forged a Hall of Fame career managing Major League Baseball's two Missouri teams by implementing a style that bears little resemblance to today's game.

Herzog's signature 1982 World Series champion St. Louis Cardinals team followed several successful yet ultimately frustrating seasons with the Kansas City Royals and was followed by two more World Series appearances with the Cardinals. All were built on speed, defense and a deep bullpen with Herzog not caring a whit about home runs.

He also managed the Angels for four games in 1974 and was something of an absentee front office executive from 1991 until he abruptly resigned a month before 1994 spring training, the club no closer to giving popular owner Gene Autry a World Series than when Herzog came aboard.

Herzog died Monday at age 92.

"Whitey spent his last few days surrounded by his family," the Herzog family said in a statement released by the Cardinals. "We have so appreciated all of the prayers and support from friends who knew he was very ill. Although it is hard for us to say goodbye, his peaceful passing was a blessing for him."

Dorrel Norman Elvert Herzog grew up in New Athens, Ill., to working-class parents. As a teen, Herzog, called Relly by family and friends, would hitchhike to Sportsman's Park to watch Cardinals games, arriving early enough to snatch up batting practice balls that he and friends would use during pickup games.

The left-handed Herzog starred in baseball and basketball in high school and was signed by the New York Yankees after graduating in 1949. He picked up the nickname "Whitey" from a broadcaster while playing in the minors.

In four years he advanced from Class D to Class AAA, but after the 1952 season he was drafted into the Army and spent two years in the Army Corps of Engineers. Upon finishing his hitch and returning to baseball in 1955, Herzog had a breakout season, batting .289 with 21 home runs and 98 runs batted in at Class AAA Denver.

During spring training he was taken under the wing of Casey Stengel, the legendary Yankees manager who won seven World Series titles from 1949 to 1958 and whose pearls of wisdom in fractured English were priceless.

"When I met Stengel, it was like an enlightening thing because I would go to bed at night, instead of thinking about girls, I would be thinking about what the hell he talked about all day," Herzog said during his 2010 Hall of Fame induction speech.

"Casey and I used to sit in the press room during spring training and every night we would have a few pops and talk baseball, among other things. And Casey told me so many things that I've been using the rest of my life. For some reason he knew I was going to be a big league manager."

Herzog never got to play for the Yankees. He was traded shortly before opening day in 1956 to the Washington Senators and batted .245 as a starting outfielder. He played eight seasons in the majors, batting .257 with 25 home runs and 172 RBIs in 1,614 at-bats with the Senators, Kansas City Athletics, Baltimore Orioles and Detroit Tigers.

He spent the 1964 season scouting for the Athletics, then served as the New York Mets' first-base coach in 1965 before becoming director of player development for the next six years. Herzog was passed over in favor of Yogi Berra to replace deceased Mets manager Gil Hodges before the 1972 season and was hired to manage the Texas Rangers a year later.

Herzog gave little indication he'd become a Hall of Fame manager — the Rangers were 47-91 when they fired him because Billy Martin became available. In 1974, he became the Angels' third-base coach and managed the team for four midseason games after Bobby Winkles was fired and before Dick Williams was hired, going 2-2.

Royals general manager Joe Burke gave Herzog his first big break, hiring him in late July after firing Jack McKeon despite the team's 50-46 record. The Royals — as did the Cardinals in the 1980s — played on artificial turf, and Herzog recognized that players with speed and slick gloves adapted best on a surface that saw ground balls zip through the infield.

"The key to having a good team on turf is that you have to have a real good-throwing shortstop, because he needs to play deep and make a lot of throws from the hole," Herzog said.

Freddie Patek was Herzog's shortstop in Kansas City, but it was the player standing next to him at third base that made the biggest impact: George Brett, who won the American League batting title in 1976. Seven Royals players stole at least 20 bases that year while the team home run leader was Amos Otis with a paltry 18.

The Royals won the American League West in each of Herzog's first three full seasons, yet never reached the World Series, losing to the Yankees in the AL Championship Series each year. In 1979 the Royals failed to make the playoffs and Herzog was fired.

He didn't go far to find a new gig, replacing Ken Boyer as the Cardinals' manager 51 games into the 1980 season. That fall he was named general manager as well and enthusiastically embraced the role during the winter meetings, trading six pitchers, three catchers, two infielders and one outfielder for four pitchers, two catchers and an outfielder.

Among the noteworthy names that came and went were Bruce Sutter, Rollie Fingers, Ted Simmons, Terry Kennedy, Gene Tenace and Leon Durham. That offseason, Herzog also signed free agent Darrell Porter, who had been his catcher in Kansas City. In 1982, Porter was voted most valuable player of the NLCS and the World Series for St. Louis.

"Whenever I would get discouraged and start feeling like I just didn't belong in the major leagues, Whitey was always there to lift my spirits," Porter said. "He would tell me, 'You're my catcher. You'll come back and you'll be all right tomorrow,' and just the way he said it made me believe in myself."

A year later, Herzog shuffled more Cards, making moves that set the stage for three World Series appearances by trading for acclaimed shortstop Ozzie Smith and outfielders Willie McGee and Lonnie Smith while also re-signing starting pitcher Joaquin Andujar.

The roster was set for full-fledged " Whitey Ball," as it was known, and the 1982 Cardinals hit just 67 home runs while stealing 200 bases to the soundtrack of "Celebration" by Kool and the Gang. St. Louis won the World Series in seven games over the Milwaukee Brewers.

The Cardinals ran even more when Herzog plugged Vince Coleman into the leadoff spot. The outfielder had 110 of the team's 314 stolen bases in 1985 and another title might have resulted but for one of the most infamous blown calls in baseball history.

St. Louis led their intrastate rival Royals three games to two and by one run in Game 6 of the World Series when Jorge Orta led off the ninth with a ground ball to Cardinals first baseman Jack Clark. Pitcher Todd Worrell covered first, Clark tossed him the ball in time to record the out ... except that umpire Don Denkinger called Orta safe.

The shaken Cardinals imploded, losing that game and Game 7 the next day. ''We had the damned World Series won,'' Herzog said.

St. Louis returned to the World Series once more under Herzog, losing in seven games to the Minnesota Twins in 1987. Herzog resigned halfway through the 1990 season, lamenting that he could no longer motivate his players.

"I was totally embarrassed by the way our team played," said Herzog, whose lifetime record was 1,281 wins, 1,125 losses and three ties. "I just feel very badly for the ball club, the organization and the fans."

The Angels hired Herzog in September 1991 as senior vice president of player personnel, hoping his evaluation acumen could elevate a franchise that had never been to a World Series. Instead, in his 2½ years on the job the Angels regressed. Herzog was frustrated by payroll constraints imposed by Gene and Jackie Autry and the burgeoning role of agents in negotiating contracts.

"Whitey is the type who, when he wants to get something done, he wants to do it now and may not be a diplomat if he's prevented from it," Angels manager Buck Rodgers said at the time. "If the time was right, he wanted to feel he could go get that one more guy."

Herzog had developed a friendship with Gene Autry as an Angels coach years earlier, and the Singing Cowboy allowed Herzog to work out of his home in St. Louis. The arrangement proved problematic, even though team president Richard Brown insisted to the end that it wasn't. "I keep a beeper with me at all times," Brown said the day Herzog resigned. "It has an 800 number. I was never out of contact with Whitey."

Retired from baseball, Herzog was never far from the game. He'd surface each spring — and sometimes during the season — and was always willing to voice his opinions.

"The state of the game in baseball is about as bad as I've ever seen it," Herzog told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch shortly before turning 90 in 2021. "It's all strikeouts and home runs and a high number of pitches."

"And then, the commissioner [ Rob Manfred], who's never worn a jockstrap, has all these rules … and the way every manager is using his bullpen now … out of 54 outs every night, you've got about 22 strikeouts between the two teams and 10 walks. So you've got 32 guys every night that don't hit the baseball."

Teams on average hit about 170 home runs and stole 85 bases in 2022, the polar opposite of his 1980s teams. Herzog died believing Whitey Ball was more exciting than the current brand of baseball.

"The fans loved it," he told the Post-Dispatch. "I still have fans every day that want to shake my hand for giving them exciting baseball for 10 years. At the grocery store, at the gas station, at the bank … everybody who recognizes me remembers the '80s."

Herzog is survived by his wife of 71 years, Mary Lou, children Debbie Urick, David Herzog and Jim Herzog. His grandson John Urick played six seasons in the minor leagues.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

©2024 Los Angeles Times. Visit latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.